Introduction

On December 20th 2016, after many of us had already shut down for the holidays, Prime Minister Trudeau and President Obama jointly announced a ban on offshore oil and gas activity in the Arctic.

At the same time, though even less reported, Trudeau announced his intent to revise our Arctic policy, replacing the Harper Government’s “Northern Strategy” with a new “Arctic Policy Framework”.

What are the implications of these announcements, to the Canadian Arctic, and to the Government’s commitment to Northern development?

In order to understand these implications, we need to consider:

– The current status of the original (Harper) Northern Strategy,

– The current business situation in Arctic Canada,

– The philosophy and priorities of the current (Trudeau) Government, Territorial and Aboriginal Governments, and

– The Donald Trump factor.

With that, we can make thoughtful predictions on what the new Northern Strategy framework is likely to look like, and what the implications are to those people and companies with a responsibility or an interest in responsible Northern development.

The Harper Northern Strategy – a Post Mortem

Everyone knows how special the Arctic is to Stephen Harper. His annual summer Arctic tours were well covered by the press, in part because of the big-ticket announcements he made, and in part because of the breath-taking Northern vistas that backdropped those announcements.

Perhaps not quite so broadly known was Harper’s true personal passion for the Canadian Arctic, how he loved to pore over maps and point out place names and features to anyone who would listen. I’m simplifying of course, but Harper’s vision of the Arctic was one of geography, of sovereign territory, and of resource development. A means to achieving his goal of becoming an energy superpower.

This is not meant to criticize the Northern Strategy, which was originally penned by Government officials in INAC as a plan for addressing the opportunities and issues facing Canada’s North in an era of climate change (which is impacting Northern Canada more than twice as much as us in the South) and globalization.

The Northern Strategy was described in terms of four themes:

– Exercising our Arctic sovereignty

– Protecting our environmental heritage

– Promoting social and economic development

– Improving and devolving Northern governance.

While several projects and initiatives were launched (and some completed) under all four of the themes, Harper’s favorite (and indeed the favorite of Canada’s defence industry) was the big-ticket Sovereignty theme.

|

Arctic Sovereignty |

Environmental Heritage |

||

| Search for Franklin’s ships

Arctic Offshore Patrol ships UNCLOS Survey CF Arctic Training Centre North Warning System ISS Nanisivik refueling depot Polar Class Icebreaker |

Complete

In progress Complete Complete In progress Delayed Delayed |

Contaminated site remediation

Polar Comms and Weather Sat |

In progress

Cancelled |

|

Social and Economic Development |

Northern Governance |

||

| Nutrition North program

CANNOR funding Deh Cho Bridge Mackenzie Valley Fibre Inuvik-Tuk All-Weather Road |

In progress

In progress Complete In progress In progress |

NWT Devolution agreement

Nunavut Land Claim agreement |

Complete

Complete |

Despite his Northern Strategy accomplishments, Harper’s management of the Northern Strategy was not without criticism, mainly on his emphasis on the sovereignty aspect, and on claims that he was big on promises, short on delivery. Those two issues are related: The sovereignty focus led to defence procurement announcements, which a) tend to be expensive, and b) are prone to get mired in the Gordian Knot of Canadian defence procurement. But that’s another story.

Sovereignty approach criticism also came from Canada’s northerners who argued that “sovereignty begins at home”, that the best way to exercise and ensure sovereignty of Canada’s North was to take care of the people and the Northern communities. ITK President Mary Simon explained that a twenty-first-century model for Arctic sovereignty must move beyond the outdated model of infrastructure and military bases by including Inuit as partners in defining new goals for sovereignty that include ensuring that new investments are linked to improving the well-being of Inuit.

Where are we today?

In the end, it was events much broader than Canadian Northern Strategy policy that had the biggest impact on the Canadian North.

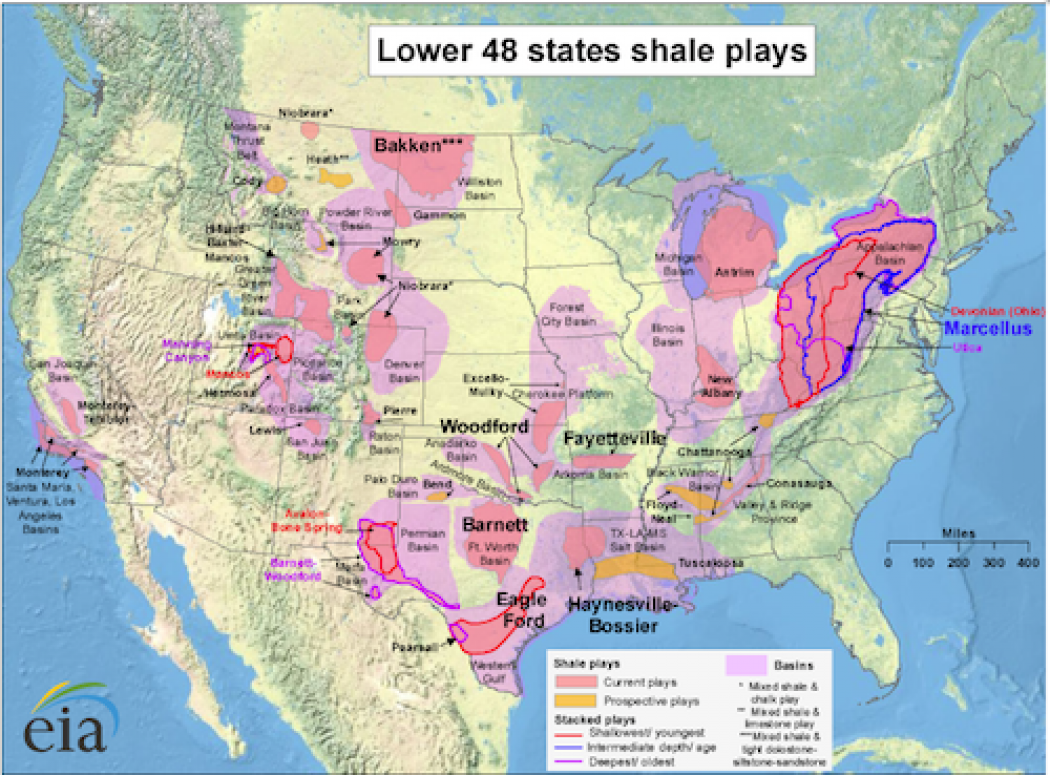

Perhaps the biggest such event was the great Fracking Rush in the US that vastly increased the supply of relatively low cost petroleum, both dropping the price of oil and representing much lower hanging fruit for energy exploration than the very difficult and expensive frontier of the North American Arctic.

In fact, the joint Obama-Trudeau moratorium announcement is largely meaningless. The conditions are simply not right for Arctic exploration today. Going forward, the Canadian ban will be reviewed every 5 years, and the Obama ban is likely to be overturned by Trump.

That, coupled with environmental concerns and a lack of social license led to Shell pulling out of the Western Arctic, and with it the further decline of the service industry related to energy activity, including NTCL (which also serves as a vital sealift transportation link for western Arctic communities) becoming insolvent. A time and an opportunity for innovative new solutions like Airships perhaps?

Another 2016 casualty was the closure of the wheat port in Churchill Manitoba, Canada’s only deep sea arctic port. Here free market economics was the cause, spurred by the end of the Canadian Wheat Board monopoly. Well established and better rail connected ports in Thunder Bay and Vancouver are more efficient, and the private Omnitrax railway to Churchill cannot compete without government “nation building” subsidies.

If there was one “positive” in 2016, it was that climate change continued its accelerating march, which continues to open up the Arctic to tourism opportunities. This year saw the maiden NWP voyage of Crystal Serenity and its sold out complement of 1000 passengers, some of whom were disappointed that they encountered NO ice along the entire route.

A Change of Leaders, A Change of Focus

When the Liberals under Justin Trudeau were elected to form the next government, they won all three northern Territorial seats. Whether Trudeau views the Canadian Arctic as important as did Harper is debatable, but there is no doubt there is a change of focus and a change of approach.

Whereas Harper’s Arctic was all about land and sovereign territory and the resource wealth they hold, Trudeau’s Arctic is all about the people that live there, and their pressing socio-economic needs.

Going beyond consultation, Trudeau has shown signs that he is interested in true partnership with the Aboriginal land owners. That said, intention is often easier than follow-through, and Trudeau was criticized by all three Territorial Premiers when he announced the Arctic oil exploration moratorium without any prior consultation or warning.

Don’t assume that the Northerners are necessarily against arctic oil development. I recall attending a panel session on Arctic oil development at the International Polar Year Conference back in 2012. On the panel were executives from big oil, Arctic policy bureaucrats from Ottawa, and an Inuit leader. They faced the usual and predictable questions from the audience exploring various risk scenarios to do with potential oil spills and the like. The oil executives would defend their safety plans and technology, the Inuit leader would explain just how devastating such an incident could be not just for now but for generations to come, and the bureaucrats said bureaucratic things. Then one audience member posed a different, more difficult question. “What if things go right? How would you feel about that?” The Inuit leader struggled. He hadn’t really expected the question. But his answer ultimately was that he’d be alright with that, in fact he’d welcome oil development, if it was done in responsibly and in a partnership model. So again, don’t assume Northerners are like the Seattle kayakers and that they oppose energy development if it is done right.

The Trump Factor

So far Trudeau has gone out of his way not to do or say anything that would offend or rile up Donald Trump. That said, it is clearly going to be a huge (“yuge”?) challenge to find common ground between the two.

Strangely, one exception to that could be the Arctic. Consider what the Canadian Arctic wants and what Trump wants.

|

What does Canada’s North Want? |

What does Trump Want? |

| – Development

– Typically resource development – A boom after the bust economy |

– Glory

– Publicity |

| – Environmental protection

– A close bond between people & the land – A very fragile environment – Dramatically affected by climate change |

– Power

– Develop America – Do deals with other countries – Defeat his enemies |

| – Peace and security

– As do we all |

A wild card is Trump’s relationship with Russia where on one hand he is signaling he want to do business with Russia including on Arctic energy development, and on the other he is talking about rebuilding the US military, including the nuclear arsenal. Interestingly, Canada’s Foregn Affairs minister Stephane Dion is also pushing for cooperation with Russia in the Arctic.

It looks like a good time to sell and launch bi-national development megaprojects. For example:

– Keystone, for which Trump has already signaled his support,

– The Northern Marine Transportation Corridor, which was originally conceived not as a Canadian project, but as a bi-national project along the lines of the St. Lawrence Seaway, and

– The next-generation NORAD system, which would be a chance for Trump to put his stamp on defense spending.

This might also be an opportunity to attract green economy investment and talent from the US, but that too is another story.

The new Northern Strategy Framework

While the new framework has not yet been announced, the analysis provided above provides some strong hints as to what it is likely to look like:

– A focus on the people

o Creating employment options

o Building community capacity

o On building strategic infrastructure

– A focus on partnership

o Between the people and the developers

o Between the Territories and the Feds

o On Transportation, communication and defence of Canada and the North

– A focus on the environment – Northern style

The phrase “employment options” is interesting. There are still a large proportion of the Inuit who have not yet chosen to join the wage economy and it is not being forced. However. There are opportunities to create jobs in a number of sectors including mining, energy, fisheries, transportation (air, marine), telecommunications services, tourism, government services, the arts, defence, building construction and maintenance, and the knowledge economy.

“Community capacity” includes health, providing affordable housing options, education, and justice.

Implications for Developers

There are two main implications for companies and people with an interest in Canadian Northern infrastructure development:

1. The Northern perspective and rights really do matter. It is no longer (if it ever was) sufficient merely to think of the Arctic as a merely a site in which to install systems and facilities conceived in the South. Domain knowledge is important, including understanding the needs and wishes and culture of the people. Don’t expect southern solutions to work. Consultation is not enough, you need to partner with those who own the land.

2. The Northern Strategy “opportunity” has not gone away. In fact it has grown considerably. Think of the new focus on the people as an increase in scope compared to what was already there. The defence needs have not gone away, in fact they have grown. But you need to partner on those as well. And there are exciting new opportunities for large scale PPP strategic infrastructure projects (those that will foster local economic growth once world conditions allow). These include the Northern Marine Transportation Corridor, private icebreaking, airship transportation networks, etc.

Conclusion

When having a first conversation about the Canadian Arctic with somebody, I often describe it in terms of a redefined acronym RSVP: Remote, Severe, Vast, and Populated.

The acronym could better be spelled now as rsvP. The focus really is on the people.

Prime Minister Trudeau has not abandoned the Northern Strategy, he has expanded its scope. The new focus opens up new opportunities, new challenges in the areas in community development (health, housing, education and justice).

There are also large new opportunities, both nationally and bi-nationally, for strategic infrastructure megaprojects that have a return on investment that will be realized once the global economic conditions are right. The preferred approach for many of these will be Private Public Partnerships. In the long run, these investments will stimulate further development and further development opportunities in Canada’s Arctic.

Finally, Russian détente under Trump’s presidency are likely to open up circumpolar cooperation export opportunities, primarily in the mining and energy sectors.